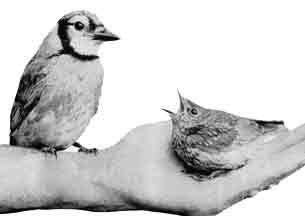

An Avian Creche

Bonnie, the bluebird, and Vee, the wood thrush, helped to operate

By H.R. IVOR

Nature Magazine, August-September 1944

Until you have served as foster parent to eighteen nestling birds at once you have never really been busy. Fourteen feathered parents should have been trying to quiet the quivering wings and satisfy the coaxing calls of this troop. They would have had to work from dawn to dark to do this. So did I.

Why, one might inquire, take over such a task? The answer is in the interests of science. There is much that is not known about the intimate life histories of our birds. As Dr. Lee Crandall has pointed out, the bird in the wild does not show its true personality. "This personality," he says, "we usually get from a hand-reared bird because it acts toward one who rears it as it would toward its own family. In no other way can one get on a bird's own level."

To get on this avian "level," and to try to fill in gaps in our bird knowledge, I maintain an aviary not far from Toronto, Canada. There is a summer aviary, and a winter one. There birds are kept in a state of semi-captivity, while in the woods and undergrowth all about, and in nesting boxes, birds rear their families in a free sanctuary. Each year a few nestlings are reared by hand for study, and with the hope of obtaining information that will help us better to protect and increase our bird population.

UNU, THE BLUEJAY, VISITS WITH VEE, AS A BABY

Thus I acquired the hungry group. The first was an eight-day-old bluebird, adopted before the middle of May. About mid-June the nursery was taxed by the addition of three blue jays, three bobolinks, three cardinals, two Baltimore orioles, one cowbird, three wood thrushes and three veeries. None were more than ten days old, and fear of man was barely dawning in them.

Usually no more than three or four nestlings are hand-reared at one time because the first, and often the second, nests of many birds are robbed by natural enemies. This year, however, there seemed to be a scarcity of predators, and most birds in the sanctuary succeeded with their first nests. Thus the population of the nursery was larger and more varied than ever before.

Feeding is done with a partly hollowed elderberry cane that is dipped into prepared jars of feed. This feeding stick still brought coaxings from the baby bluebird after six weeks in the winter aviary, which she shared with an old, unmated wood thrush and a pair of bluebirds until the eighteen nestlings moved in. Other birds had been moved to the summer aviary.

By this time the little bluebird had acquired a name, Bonnie. She was a lovable bird and indeed bonnie, so the name fitted. When the new nestlings arrived and began setting up a chorus of appealing infant bird calls, stretching wide their exquisitely colored mouths, some lined with orange, some with pink, Bonnie took an immediate interest. She watched me curiously, flying to my hand expectantly when she saw the food-stick dipped. Yet when its contents were given to another she did not seem disappointed. Indeed, after this had happened several times, and the stick was finally offered to her, she took the contents, turned to the bird mite next to her and popped the food into the waiting mouth.

With this Bonnie became my assistant. She would take the food and hop to first one nestling and then another, none of which was a bluebird. No baby received more than two helpings, either, and if only one was near and had had a second serving, Bonnie would hunt up one that had not been fed. She played no favorites, rarely forgetting one, and soon taking the food from the jars instead of the stick.

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version