Digging For Birds, Page 3

By ARTHUR NEWTON PACK

On the following day the wind had swung to the northwest and the swells rolled ever higher in our so-called harbor. It was too rough for our steel outboard launch, but the camera hunters, with Bill, the engineer, set out in the dinghy with a small outboard motor to cruise toward the northern end of the island. There we clambered like human flies up a steep cliff where a pair of Peale's falcons shrieked and circled about us. A bald-headed eagle sailed by, and the falcons attacked him in mid air. All about were burrows. But what burrows! We now had shovel and crowbar besides the axes, but even with them the digging out was hard work. At last we unearthed one nest, only to find it that of another rhinoceros auklet. Above, in the thickets, we came upon the remains of Cassin's auklets eaten by the falcons, but no puffins. We had hoped to find here the nest of the marbled murrelet, which has only lately been discovered, but in this we were unsuccessful.

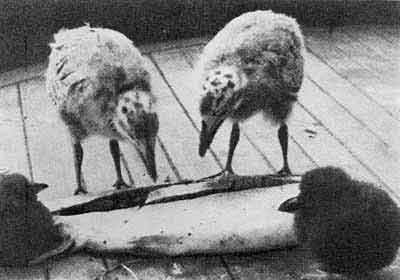

WHAT A DAINTY DISH TO SET BEFORE A GULL

On the west side of the island, where the long waves from the open ocean crashed endlessly against sheer cliffs, it was clear that no boat could land. Our route must be overland, up the steep fir-clad slopes and then, if possible, down again. Cameras were placed in packsacks, ropes were coiled, and the heavier digging equipment left behind. Up we plodded, stopping now and then to rest our heavy packs. The slope seemed endless. An hour passed and then the roar of waves and the keen whistle of the sea wind suddenly smote our ears. We burst through the last trees and halted abruptly, fearsomely, upon the very brink of awful destruction. Here was no corresponding slope-our mountain had no other side-only a sheer abyss carved by the centuries of storm and stress into plunging nothingness. Far below the blue-green ocean beat itself into shattering spray arid the cries of ten thousand birds filled the air. For a moment we stood, breathing deeply, thrilling to the elemental awfulness of Nature untamed. Then carne the call of what we had set out to do. There below us, on a narrow, wind-carved ledge, were the high, built-up nests of pelagic cormorants, where sat the snaky-necked mother birds. Beyond them, on still narrower shelves, stretching out to the sheer plunging edge, clustered the murres . Their sleek coats of black and white stood out against the gray and brown of the rocks. Their single, top-shaped eggs lay all about beneath the feet of the struggling, pushing adult birds. Only that strange pyriform shape could keep the eggs from rolling off into space. And how could each mother possibly know her own?

A RHINOCEROS AUKLET THAT WAS PULLED OUT IF ITS BURROW

We crawled along a windswept ledge hollowed out like a half cave. Now that the material for real pictures was before us, even slippery footholds and crumbling hand grips seemed easy. The keen wind clutched in vain. Back and forth we made our way, stopping to take photographs in that wealth of material and against the background of swirling sea and sky. "Look!" cried Mrs. Pack. "Below, on the rocks-sea lions!" She worked her precarious way downward bit by bit while the Skipper repeatedly fastened and unfastened his rope to act as a brake. Then, as the little party approached, the watchful bull seemed to give the signal and with one accord the ungainly creatures flopped to the edge and dived off into the boiling waves. The bull himself waited. Was he courageously guarding his harem from the rear, or only too lazy and comfortable to be stampeded? Two cameras were working now. "Action, action, please!" yelled Finley, and he waved his hat at the ponderous old sea lion.• He looked around, emitted a gaping roar, and then hitched himself to the edge. One instant he poised, and then stretched out his sinuous neck and dived straight and clean into the sea. About him there the others gathered, yawping, until the combined sound of their cries drowned out the lighter swish and splash of the• waves and only the hollow booming of the surf kept up a bass accompaniment to the turmoil.

I looked back. The fir trees on the edge of the abyss were far above us. The myriad startled birds we had disturbed circled overhead with indignant cries. It was time to stare back. Without the Skipper's rope, I believe that I, for one, would be there still, but we scrambled and clung and slipped and held one another until at last, hot and panting, we reached the beginning of the forest. Then down through the trees our stumbling way led. Once more the Westward lay gently rolling on the swells. Next day we sailed for new adventures in inland waters.

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version